One male and two female royal gramma swim in a broodstock tank at the Marine Science Magnet High School in Groton. Photo: Haley Pratt

Swimming rainbows of purple, magenta, orange and yellow on Caribbean coral reefs, royal gramma are one of the most popular fish for home aquariums.

But the journey from the reef to the pet shop is often fatal, both for the little fish and their marine habitats.

“In some cases, some very destructive methods are used to catch the fish,” said Paul Anderson, research scientist at Mystic Aquarium leading the project. “Sometimes cyanide is released on the reef to stun the fish, or it will be dynamited. Then they change hands so many times along the way. We’re trying to improve the care of the fish all along the chain.”

In a project funded by Connecticut Sea Grant, the aquarium has teamed up with the Marine Sciences Magnet High School in Groton to raise royal gramma through aquaculture, reducing pressure on those living in the wild and potentially reducing mortality rates for the fish taken home by hobbyists. Now in its third year, the project has expanded the school’s aquaculture projects from seafood production into ornamental fish husbandry, opening up a possible new career path for students.

“More hobbyists are now asking for sustainably caught fish,” said Eric Litvinoff, director of aquaculture at the school.

Two aquarium staff, Vince Vacco and Megan Armstrong, work regularly at the school with the students, and also oversee the care of the brood stock and labs where food for the project is grown. That includes several strains of algae fed to the tiny microscopic animals -- copepods, brine shrimp and rotifers – that are in turn fed to the royal gramma.

During the first year, the project focused on raising clown fish, so students and the aquarium staff could learn the aquaculture methods using established protocols with a species that’s relatively easy to grow. The second year, the school took in its first batch of royal gramma, a more challenging species due to its aggressive behavior and cannibalistic tendencies. The first year, all of the larvae were eaten by the adults.

“This year, we’ve developed a larvae collector, so that the eggs get sucked into an uplift tube and into a container that keeps the adults away,” Anderson said.

Others have developed methods of raising royal gramma through aquaculture, he said, but they aren’t in widespread use because they are too costly and labor intensive to be practical.

“We’re not the first ones to try to breed these guys, but what we’re trying to do is develop easy protocols that the industry can adopt,” Anderson said.

There are two groups of royal gramma now at the school. In one lab, six tanks are lined up on shelves behind a black plastic curtain, each with different ratios of males to females. One might have one male to two females, while another has one male and one female, and a third, one male to three females. The purpose, Anderson said, is to determine which ratio proves to be the most effective at reducing aggression and producing the most eggs. Cameras are set up to record whether the male is successful at luring females into the nest.

“We’re recording their courtship behaviors,” said Anderson. “The male builds and maintains the nest, and then does a couple of U-turns and sometimes quivers his tail in front of the female.”

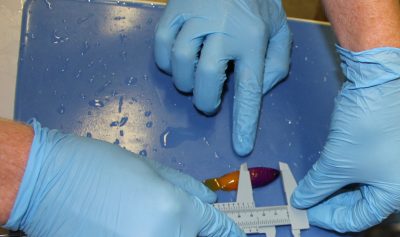

In another room, 35 younger fish swim in a large tank divided into cubicles to keep them apart. On Oct. 25, Vacco, Armstrong and two students at the high school – seniors Johann Heupel and Matthew Parizo – worked together on measuring and recording the size of each fish, then injecting an elastomer white tag into the males.

“I want to do marine science as a major in college, so it’s awesome to get such close access to this kind of active work,” said Heupel.

In addition to Sea Grant, Anderson noted that support from the project also came from the Joint Aquaculture Research Laboratory, a member of Rising Tide Conservation. That is an association of research labs, public aquaria, and commercial members working to bring more ornamental fish raised through aquaculture to market. A third partner is the Marine Sciences Department of the University of Connecticut, which was awarded a National Science Foundation grant to provide a research experience for an undergraduate student in conducting a behavioral analysis on the fish.

-- Judy Benson