New Haven – If you’ve ever assumed being a member of one of the state’s 18 local shellfish commissions is a lightweight volunteer responsibility, spending time at the annual meeting of municipal shellfish commissions on Jan. 13 would have quickly dispelled that notion.

The 14th such gathering hosted by Connecticut Sea Grant, the meeting at The Sound School brought together 46 chairmen and members of shellfish commissions from Greenwich to Stonington, along with scientists and state regulators. Intended for new and veteran commissioners alike, the meeting started with a crash course from Tessa Getchis, Sea Grant’s aquaculture extension specialist, on the status of Connecticut’s commercial and recreational harvest of oysters, clams and scallops – together valued at more than $30 million annually – and the extent of the cultivated and wild shellfish beds in state waters of Long Island Sound. She also updated the group on the Connecticut Shellfish Initiative, launched in 2014 to ensure shellfishing continues to grow in a way that is socially responsible and economically viable.

“Connecticut has some of the most productive environmentally sustainable shellfish grounds on the East Coast,” said Getchis, adding that about 70,000 acres of the Sound has been identified as shellfish beds, “and that’s just what’s been mapped.”

Because shellfish commissions oversee both recreational and commercial shellfishing in town waters, members need to understand the complexities of licenses, permits and leases of clam and oyster beds. They also need to be versed in the workings of the state Bureau of Aquaculture’s Milford laboratory that tests water and shellfish meat samples to ensure they meet health standards, and triggers closures when bacteria levels get too high. David Carey, director of the bureau, explained how staffing shortages at that lab that had slowed the testing work should be lessened as newly hired staff fill vacancies.

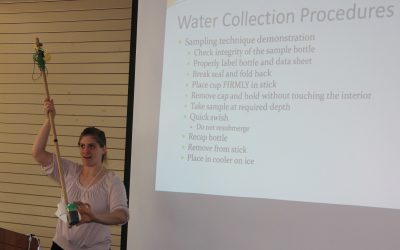

Keeping recreational and commercial beds open — and closing them when necessary to prevent people from getting sick from contaminated shellfish — depends on the commissioners’ collecting those water and meat samples regularly and after heavy rainfall and delivering them to the lab. Since it’s one their most important responsibilities, no meeting of the shellfish commissions would be complete without a review lesson on the proper way to collect the samples.

“We have to sample when the conditions are the most stressed, after a rainfall event,” said Jenifer Yeadon, environmental analyst with the bureau, as she demonstrated how to collect the water sample in a cup attached to a long dipping stick. “You need to make sure you’re sampling on the outgoing tide, about 1½ hours after high tide.”

She explained how to make sure the collection cups have the right amount of air space so the sample doesn’t have to be rejected, and offered to visit towns to train new commissioners.

In addition to the sampling duties, shellfish commissions are also required to have a management plan for their town’s commercial and recreational beds. But the state law that requires the plan doesn’t spell out what it should contain, so there is wide variety in the plans from town to town. Getchis said ongoing concern over applications from commercial shellfishermen to use areas in the Niantic River and in Stonington have highlighted the need for commissions to adopt more standardized plans that clearly spell out the process that will be followed for considering proposals. Don Murphy and Pete Harris, chairmen, respectively, of the Stonington and Waterford-East Lyme Shellfish commissions, described the high level of public interest and opposition they’ve encountered over plans for Stonington waters and the Niantic River grounds shared by East Lyme and Waterford.

“You need to have a very clear process so you can explain to the public what the application review process is,” Murphy told his fellow commissioners.

To help make the process go smoother for these two towns and others, Getchis and Carey have begun developing a model plan commissions can follow. This is crucial, they noted, as commercial shellfishermen have become increasingly interested in farming areas more visible to the public than existing beds, many of which are farther offshore.

“A lot of you have come to us asking for help, so we’re working to create a template for shellfish management plans,” Getchis said. “Having one document that you can hand the public that says, ‘this is how we manage aquaculture’ is very powerful. It will help you strengthen your processes, and it’s really important that you follow that process when you’re dealing with new applications.”

The template being created, she said, will be “general enough to apply to all towns,” but also easily adapted to the specific needs of individual communities. Getchis shared a draft template with commissioners, and invited their feedback as the final version is created.

“The more we share information and make these plans consistent, the better off we’ll be,” she said.

At the end of the five-hour meeting, commissioners were asked to give reports on their activities for the past year. They talked about numbers of recreational permits sold – ranging from 1,200 in Guilford to 250 in Fairfield – to efforts to restore oyster beds, seeding of recreational beds, shell collection at restaurants, commercial shellfishing projects, re-activation of dormant shellfish commissions and outreach to schools and the public to teach people about shellfishing. Their enthusiasm for shellfishing was evident. But they clearly also appreciated the serious and challenging side of their avocation in working with the public and managing conflicts over offshore public resources, offering advice on what’s worked in their communities.

“We had a booth at the indoor farmers market, and it was a wonderful way to reach out to the public,” said Clarinda Higgins, chairwoman of the Westport Shellfish Commission.

Click here for information about recreational shellfishing and meeting presentations.