Collaborative research on teaching and learning practices in high schools could pay off by improving coastal literacy in Connecticut.

“All residents of the state of Connecticut are intimately linked with the coastal ecosystem. Our state’s coastal resources provide food, jobs, and recreational activities” says Michael Finiguerra, a coastal scientist at the University of Connecticut. Yet, he notes, these coasts, like others, are faced with threats from pollution, altered land use, and environmental changes. A thorough knowledge about the processes that shape and change the coasts is necessary for making good decisions and policies, as well as for voter support. Finiguerra is a believer in teaching practices that both enrich the teaching experience and keep students interested. In the ecology classes he teaches, he’s taken students snorkeling, on numerous field trips, including a two-day camping trip to New Hampshire. “I love showing students that what they learn about in the textbooks surrounds them in their everyday lives.” In fact, some students have lamented that Finiguerra’s courses have transformed the outdoors from recreational to educational activities.

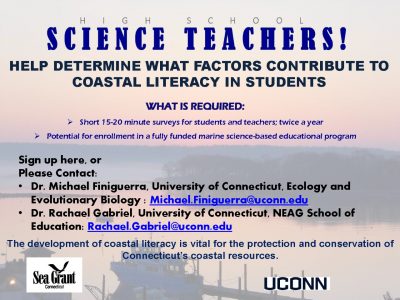

Finiguerra and Rachael Gabriel, an educational researcher also from UConn, want to improve Connecticut’s level of coastal literacy–the ability to understand, communicate and make informed decisions based on coastal sciences. But what factors most influence success in this task? We really don’t know. So, working with high school biology teachers, Finiguerra and Gabriel are implementing a Connecticut Sea Grant-funded educational research project designed to find out what factors are correlated with coastal literacy. They are focusing their efforts on high school biology classes, because classes at the high school level offer a broad opportunity to affect the overall future coastal literacy rates for the state. They also plan on testing their hypotheses to determine if including certain factors in curriculum can increase coastal literacy. “We want to create a roadmap of how schools can maximize their resources to improve coastal literacy values among their students. More informed students are, after all, more likely to protect our valuable coastal resources,” Finiguerra says.

Finiguerra and Rachael Gabriel, an educational researcher also from UConn, want to improve Connecticut’s level of coastal literacy–the ability to understand, communicate and make informed decisions based on coastal sciences. But what factors most influence success in this task? We really don’t know. So, working with high school biology teachers, Finiguerra and Gabriel are implementing a Connecticut Sea Grant-funded educational research project designed to find out what factors are correlated with coastal literacy. They are focusing their efforts on high school biology classes, because classes at the high school level offer a broad opportunity to affect the overall future coastal literacy rates for the state. They also plan on testing their hypotheses to determine if including certain factors in curriculum can increase coastal literacy. “We want to create a roadmap of how schools can maximize their resources to improve coastal literacy values among their students. More informed students are, after all, more likely to protect our valuable coastal resources,” Finiguerra says.

So far the team has contacted many STEM teachers through a variety of ways and also set up a booth at the Connecticut High School Teachers 2016 meeting. They want to attract science teachers interested in participating in the project and networking with peers. It is important that they get a wide range of participating schools, not just those that have marine science programs. Students in science classes taught by those teachers will be assessed on their knowledge of coastal processes. The teaching practices used and other information from surveys will be analyzed with the student assessment results to identify factors involved and approaches that may work best in the classroom. The project has another year to go, and the researchers expect to expand their efforts in 2017. A web site for this project has been created, at which teachers can find out more and sign on to participate: http://coastalliteracy.uconn.edu

So far the team has contacted many STEM teachers through a variety of ways and also set up a booth at the Connecticut High School Teachers 2016 meeting. They want to attract science teachers interested in participating in the project and networking with peers. It is important that they get a wide range of participating schools, not just those that have marine science programs. Students in science classes taught by those teachers will be assessed on their knowledge of coastal processes. The teaching practices used and other information from surveys will be analyzed with the student assessment results to identify factors involved and approaches that may work best in the classroom. The project has another year to go, and the researchers expect to expand their efforts in 2017. A web site for this project has been created, at which teachers can find out more and sign on to participate: http://coastalliteracy.uconn.edu