Published in The Day, Nov. 15, 2020

By Judy Benson

Tell their stories. Name their names. It’s one way to start.

For several years, Connecticut Sea Grant has been looking to develop meaningful anti-racism and diversity initiatives. Just figuring out how to begin felt hard, but we have participated in conversations and contributed to the development of a diversity, equity and inclusion vision for the national Sea Grant network.

We’ve committed ourselves to learning, discussing and sorting through all the complexities to identify concrete steps we can take to make our organization more inclusive and responsive to people of color and other underrepresented groups in a way that is substantive, not superficial.

While we credit the Black Lives Matter protests this spring with renewing our engagement in these efforts, we’re in this for the long haul. Our staff have been serving on national and University of Connecticut diversity committees for several years, and within our organization we’ve started a diversity internship for undergraduates, piloted a Long Island Sound outreach program to the Hispanic community, and created Spanish versions of some educational publications, among other small steps. This is just a beginning.

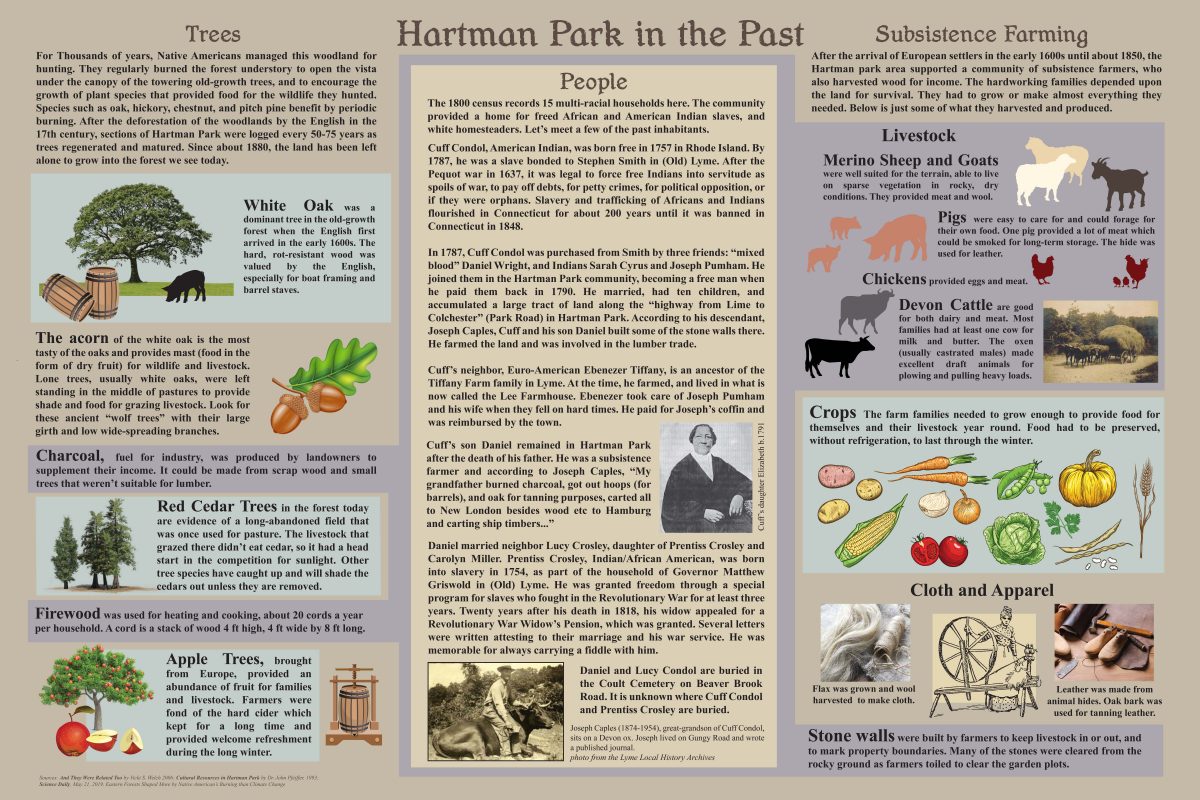

During a recent walk in the woods, I found new inspiration. It came in the form of a simple, straightforward gesture of land acknowledgement, the practice of recognizing the Native Americans and people of color who once inhabited our communities. The medium is a sign installed in June at Hartman Park, a 302-acre forest in Lyme. At the intersection of the main trails, hikers can read about a community of Native Americans, African Americans and English settlers, people named Cuff Candol, Sarah Cyrus, Joseph Pumham and Prentiss Crossley. They lived there in 1700s and 1800s, subsistence farming, hunting, making charcoal and cutting lumber. Their hands built many of the stone walls, foundations and fire pits along the paths.

Some had been slaves in local households before gaining their freedom.

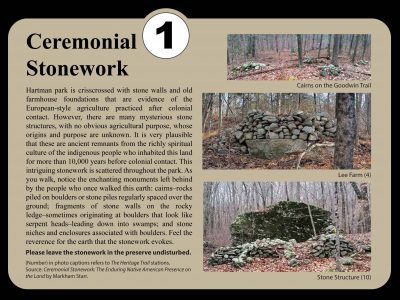

It also tells of the Native Americans who often hunted this land before colonization. They regularly burned the understory to manage the land, leaving many old growth trees colonists would later fell for the British Navy. Cairns found throughout the park today are believed to be ceremonial sites of those native people.

This is the kind of public display that more conservation and historic groups should consider providing, and there’s perhaps no better time than now. November is Native American Heritage Month, and the events of 2020 have certainly made it clear that honoring the diversity of our past and present is essential to our national well-being.

“I’m glad to give this some exposure, because we owe so much to the people from the past,” said Wendolyn Hill, open space coordinator for the town of Lyme, which owns the park.

Fascinated by what she’d learned about the history of the park, Hill wanted to find a way to share the stories with visitors. She obtained funds from the Eightmile River Wild & Scenic Watershed for the sign project, and drew on the work of several researchers for the content.

“We definitely want to be inclusive and want more people to visit our preserves and feel welcome,” she said.

Yale University Professor Gerald Torres believes land acknowledgement is a worthwhile action. One of the nation’s leading environmental justice scholars, Torres speaks about the value of land acknowledgement in the upcoming Fall-Winter issue of Wrack Lines, Connecticut Sea Grant’s biannual magazine.

“Just being conscious of the native people on whose land the state and the various towns sit is an excellent first step,” he says in the interview.

For this hiker, the sign at Hartman Park reminded me that diversity has been part of the national fabric for centuries. Our work today continues this great tradition. We have much to do, but we have a strong foundation to build upon.

For information about Hartman Park and other Lyme preserves, visit: https://www.lymelandtrust.org/.

To receive a free print copy of Wrack Lines, the biannual magazine of Connecticut Sea Grant, send an email with your mailing address to Judy Benson, communications coordinator, at: judy.benson@uconn.edu.

Connecticut Sea Grant is based at the UConn Avery Point campus in Groton, which is located on Mohegan and Pequot tribal land, and Lyme is located on Western Nehantic and Hammonasset tribal land, according to the Land Acknowledgement website https://land.codeforanchorage.org/.