Story and photos by Judy Benson

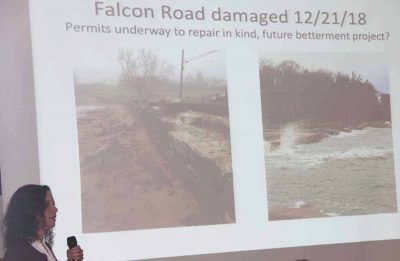

With frequent downpours flooding many of the state’s coastal roads throughout the fall and into January – including the previous day – the workshop could hardly have had more relevance and timeliness.

“I spent yesterday dealing with countless calls to my office from people saying they couldn’t get to their houses because of flooding,” said Steve Johnson, acting assistant public works director, open space and natural resource agent for Milford. “This is getting to be the new normal. Yesterday I also watched a school bus drive through two feet of water to get the kids home.”

Johnson was one of the speakers at the Climate Adaptation Academy workshop on Jan. 25 on road flooding. A capacity crowd of more than 80 municipal public works, planning and engineering officials from throughout coastal Connecticut came to the Middlesex County Extension Center in Haddam to spend the day learning about legal, environmental and practical approaches and challenges to “a problem with no easy answers,” said Juliana Barrett, coastal habitat specialist at Connecticut Sea Grant, during opening remarks. Co-sponsored by Sea Grant, UConn CLEAR and UConn Extension, the workshop is the third in a series focusing on the local ramifications of climate change and how towns can learn to cope.

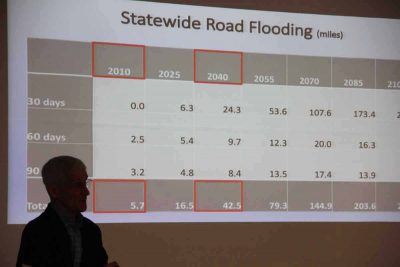

Setting the stage for the issue at hand was David Kozak, senior coastal planner in the Land and Water Resources Division of the state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. Ocean waters have been creeping onto land at accelerating rates over the past 50 years, and sea levels are projected to rise another 20 inches by 2050 and about four feet by 2100, he said. “Sunny day flooding,” when roads become submerged by high tides rather than heavy rains and storm surge, is becoming more common, he added.

Caught between the encroaching waters and dry land are salt marshes and roadways through low-lying coastal communities. Finding ways so that both can continue to exist on the Connecticut shoreline will be one of the main tasks of coastal town officials for the coming decades, Kozak said.

“Marshes are incredibly important to Long Island Sound,” he said. “There is a nexus between marshes and roads, so we need to look at these two things together.”

To preserve marshes, adjacent areas must be kept free of development so they can migrate inland. Elevation and other improvements to nearby roads must allow for tidal flows into and out of marshes, while at the same time protecting homes and businesses. The challenge is compounded by steep terrain near the shore in many areas of the coast, he noted.

“Loss of our marshes potentially would change the ecology of Long Island Sound,” he said. “We have to look for marsh migration conservation opportunities, and modify the hydraulic connections at road crossings.”

The state needs to create an inventory of the most critical marshes and adjacent areas for potential conservation. The biggest challenges, he said, will be dealing with the many flooded roads that are the only access to beach neighborhoods. One new tool that will help land use managers, he said, is a digital road flooding and marsh migration viewer being created by CLEAR. It is slated for release this spring.

After Kozak’s talk, Janice Plaziak, town engineer for Guilford, joined a Johnson and a representative of a local engineering firm in giving specific examples of how they are dealing with road flooding problems in their towns.

“We have 10 roads that have been identified as flood prone, and three have been elevated so far,” Plaziak said. Some of the roads are the sole access to neighborhoods of large homes that make significant contributions to the town’s tax base, she noted, so not fixing the problems would devalue the taxable value of the properties.

Working with the state Department of Transportation on state roads and bridges prone to flooding has also been challenging, speakers said, because the improvements aren’t being designed with long-term sea level rise projections in mind.

Jeff Jacobson of the Chester-based civil and environmental engineering firm Nathan L. Jacobson & Associates said in many cases, the solutions proposed for flooding problems are short-sighted, failing to account for increasingly severe climate change impacts along the coast in the coming decades.

“The longer term solution that our political leaders don’t want to talk about is shoreline retreat,” he said.

Other speakers agreed, advocating for policies that would enable more buyouts of vulnerable neighborhoods, as happened in the Old Field Creek area in West Haven after Superstorm Sandy in 2012. Officials from the DOT came out of the workshop with new ideas and perspectives about how to work with town officials in moving forward on road flooding issues.

But road flooding isn’t just a public works challenge. Read Porter, senior staff attorney with the Marine Affairs Institute at Roger Williams School of Law and the Rhode Island Sea Grant Legal Program, said towns can be held liable for failing to fix road flooding, but the best way to do that can be difficult to determine. Municipalities, he said, have basically three options: elevate the road so it no longer floods, discontinue use of the road through a legal process, or abandon the road by not maintaining it. The legal implications, pluses and minuses of each of the options is detailed in a fact sheet developed by two legal fellows from the Roger Williams law school under the direction of Porter for the academy.

“The legal questions you have to consider can be really challenging,” he said.

After Porter’s talk, two officials with DEEP’s Land and Water Resources Division – Environmental Analyst Harry Yamalis and Assistant Director Jeff Caiola — presented several solutions towns could use to alleviate road flooding and preserve marshes at the same time. These include use of tide gates to direct water flow into and out of the marshes, as well as road elevation. The challenge, Caiola and others said, is to design a project that will preserve marshes and be resilient as the coastal environment continues to change.

“The struggle we see is when houses get built on the shore and then rebuilt twice the size and harden in place,” he said. “Towns are struggling to keep their tax base. There is a need to educate the public.”

During a question-and-answer session, audience members said the problems along the Connecticut coast are much bigger than road flooding. Dealing with the multiple effects of climate change is likely to be complicated, expensive and painful.

“We’ve got to face the facts that are coming our way,” said Sidney Gale, a Guilford resident. “We don’t have to be heroes, but we can’t be cowards.”

Attorney Jane Stahl, co-coordinator of the Climate Adaptation Academy legal workshop and moderator for the afternoon sessions, agreed that the road flooding problem is just one small piece of the climate change challenge. Nonetheless, she noted, it offers a tangible means of engaging residents who may be reluctant to confront the reality of climate change. She urged attendees to advocate with lawmakers for more proactive state initiatives to prepare for climate change impacts.

“While we’re putting our finger in the dike day in and day out,” she said, “there doesn’t seem to be anybody looking at the longer term prospects. It’s not just the guy who has to drive through the puddle every night to get to his house. It’s the guy who lives down the street who doesn’t have the puddle yet. We’ve got to get him interested.”

PowerPoint slides from the workshop presentations can be found here.

Judy Benson is the communications coordinator for Connecticut Sea Grant.