By JUDY BENSON

Coastal regions that are some of the most productive areas for fish and shellfish harvests are seeing changes in water chemistry that are in part associated with atmospheric emissions of carbon dioxide.

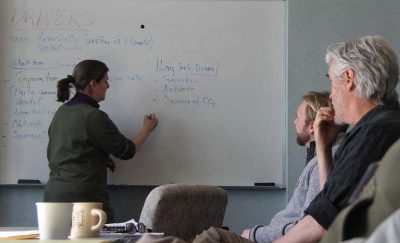

What those changes will mean for coastal communities and deciding how best to respond to them was the purpose of a three-day workshop April 10-12 sponsored by Connecticut Sea Grant and NOAA’s North Atlantic Regional Team. Titled “Coastal ocean acidification in the North Atlantic region, from science to outreach,” the event brought 40 academic, government and industry scientists to the UConn Avery Point campus, including representatives of Sea Grant programs in all of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic states. The group reviewed what is and isn’t known about coastal ocean acidification, how it differs from acidification in the open ocean, the likely effects and the various conditions that can worsen or dampen those effects.

The more acidic pH levels being found in ocean and coastal waters are one of the effects of atmospheric emissions of CO2. It is occurring as rising amounts of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels are being absorbed into the ocean, reacting with marine waters and causing bleaching of coral reefs, slowed development of marine life in larval stages and shell weakness in oysters and clams, among other impacts.

“What are our choices, and what are the consequences of those choices, in the context of what we know and don’t know?” asked Sylvain De Guise, director of CT Sea Grant, as he guided participants to make decisions on what actions should be taken.

The conference began with a presentation by Meredith White, director of research and development at Mook Sea Farm, an oyster hatchery and grower on the Damariscotta River in Maine. In 2009, she said, the farm began having “major production problems” in its hatchery.

“We had shell deformities and developmental delays in our hatchery oysters,” she said.

Water testing revealed that the pH levels of the water had dropped, making conditions more difficult for larval oysters to create shells. Now, she said, the farm adds a buffering agent to the sea water used in the hatchery to prevent that from happening, and closely monitors the pH.

“We are not the only shellfish farm or oyster grower affected by this,” she said.

Other presentations reviewed research findings about acidification along the entire East Coast, as well as variations in acidification in specific areas such as the Gulf of Maine, Casco Bay, the Great Bay in New Hampshire, the Mid-Atlantic and Chesapeake Bay and the West Coast. Changes in salinity and average temperatures in the waters of these regions are also being seen in tandem with acidification, making it difficult to determine exact cause-and-effect relationships on marine food webs, several speakers noted.

After several small-group sorting exercises, the entire group arrived at a consensus that an outreach project for shellfish farmers, fishermen, legislators and policymakers should be created to inform them about coastal ocean acidification.

“We know enough that we have to get this out there,” said Peter Rowe, director of research and extension for New Jersey Sea Grant.

De Guise said the project has about $15,000 in federal grant funds to create outreach products, which could be provided on websites, videos or other formats for the target audiences. The messages will focus on identifying stress factors for coastal ocean acidification, the timing of acidification events, local impacts, what areas need more research, risks of inaction and actions that could be taken to offset impacts, such as diversifying aquaculture crops and spreading ground-up shell around juvenile oysters.

The next step toward creating the outreach materials will include a review of the workshop summary and follow-up

discussions with the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic Coastal Acidification Network working groups. Focus group discussions with targeted stakeholders to tailor outreach products to their most immediate needs are also planned.

Judy Benson is the communications coordinator at Connecticut Sea Grant. She can be reached at: judy.benson@uconn.edu.