Shell recovery, frequent 2023 bed closures, town-by-town updates among other topics discussed

Story and photos by Judy Benson

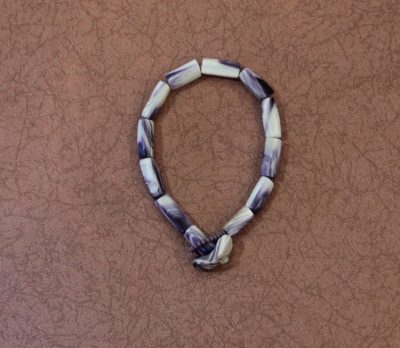

New Haven—For more than 4,500 years, indigenous people along the New England coast have turned the shells of large quahog clams into delicate purple and white beads strung into necklaces, bracelets, belts and other adornments they called wampumpeg.

For the Pequot, Narraganset, Mohegan and other tribes, these items were considered solemn emblems of commitment that were part of treaties and marriage ceremonies and taken into battle.

But when European colonists arrived, they shortened the name to “wampum” and warped its definition into the equivalent of money. Despite these distortions, the native craft survives as part of efforts to rebuild and strengthen the traditional relationship between tribal communities and shellfish.

“For us this is something that touches every generation,” said Michael Thomas, knowledge keeper for the Mashantucket Pequots, speaking to about 50 people at the Annual Gathering of Shellfish Commissions on Feb. 3. His 15-year-old son, he added, will soon begin an apprenticeship with a master wampum maker in the Narragansett tribe, Allen Hazard.

As he spoke to the shellfish commission volunteers and state shellfish regulators at the meeting, he wore a pendant around his neck with the silhouette of a turtle fashioned from wampum. He handed a wampum bracelet to an audience member and asked him to pass it around.

“There’s literally oral history attached to each piece you see,” he said. “It tells stories for us.”

Thomas’ opening talk put the day’s program in a native historical and cultural context and was met with an engaged response. Thomas answered several questions from the audience and chatted with others afterwards in the hallway outside the auditorium. While his lesson about wampum and accompanying video captured much interest, his comments about the related issue of tribal rights to shellfishing grounds also sparked a lively exchange.

“Our subsistence hunting and gathering rights were lost in the federal recognition process,” he said, referring to the 1983 agreement that established the Mashantucket Pequots as a federally recognized tribe.

His tribe as well as others in Connecticut, he said, would like tribal members—or at least those 16 and under—would be allowed to gather legal-sized clams and oysters without the local permits now required of all recreational harvesters. He considers wider access to shellfish grounds essential to preserving native culture, especially for tribal youth, and appealed to the audience for support.

“Think about advocating, especially for our young people, the ability to quahog (harvest clams) without a permit in Connecticut, as tribal members can do in Rhode Island,” he said.

In response, several commissioners and others proposed ways their towns could potentially accommodate them now.

“Guilford has no permit charge for those 14 and under, so come on down,” said Kirtland Griffin, a member of that town’s shellfish commission.

After Thomas’ presentation, state Shellfish Pathologist Lydia Bienlien gave updates on shellfish diseases of greatest interest in Connecticut, and urged commissioners to alert her office whenever they notice anything unusual in their town’s shellfish beds.

“If you see something, bring me 30 different animals,” along with details of the time, date, exact location and other conditions of the collection, she said.

“And if you learn of any projects going on with shellfish in the state,” she continued, “I would like the state to be part of it. We have very healthy oysters and clams right now, but we want to keep abreast of things, so nothing comes in without us knowing about it.”

Alissa Dragan, supervising environmental analyst with the state Department of Agriculture Bureau of Aquaculture, followed up with an overview of requirements and emerging concerns for recreational shellfishing, and noted that frequent intense rainfall in 2023 led to an unusually high number of closures of shellfish beds and an increase in water and meat sampling by her lab.

“We are reviewing the seven days of closure after rainfall rule,” she said. “We have lots of data that we think is showing that we can shorten that.”

Next came updates from each of the shellfish commissions represented. Fairfield Shellfish Commission Chairman John Short led with a by-the-numbers summary of the year’s activities: 370 shellfishing permits sold, 250 people at the annual community clamming clinic, and 70,000 oysters grown and planted in the Ash Creek shellfish restoration area.

He and several others noted that due to the multiple rainfall closures, permit sales were down from previous years. In the Niantic River, the Waterford-East Lyme Shellfish Commission opened scalloping season for the first time in several years, with modest success, said Larry Tytla, commission vice chairman. Both Steve Bardish and Brian Yarmosh, of the Norwalk and Stamford shellfish commissions, respectively, raised concerns about the potential impacts of the Walk Bridge construction project on Interstate 95 on nearby shellfish beds in the Norwalk River.

In Stonington, commercial growers had a “spectacularly difficult year,” said Don Murphy, commission chairman, due to frequent rainfall closures and a broken sewer pipe that closed lease areas in the Mystic River for several weeks.

“There were long periods including over the holidays when they could not bring their product to market,” Murphy said.

For the coming year, he added, the commission is looking forward to opening a new recreational shellfishing area that will be easily accessible to the public and is moving to an online permit sale system.

The meeting concluded with an overview of progress in expanding the state’s limited shell recovery program. Michael Gilman, assistant extension educator for CT Sea Grant, said the term “shell recovery” is preferred over “shell recycling” because it more accurately describes the purpose of the activity—to recover shell from restaurants and wholesalers and return it to coastal waters after curing to restore habitat for juvenile oysters. Gilman leads the CT Sea Grant’s efforts to work with partners on developing the shell recovery program.

Tim Macklin, founder of the nonprofit organization Collective Oyster Recycling and Restoration (CORR), said his group is now collecting shell from 30 restaurants, wholesalers and festivals mainly in Fairfield County, and bringing it to a former quarry in East Haven to be cured for at least six months. The state Bureau of Aquaculture oversees the placement of the cured shell into the state’s natural shellfish beds.

Macklin said his group is eager to help shellfish commissions across the state educate the public about shell recovery, and start collecting and curing shell in their towns.

“We’re basically here to facilitate as much shell recycling in Connecticut as possible,” Macklin said. “We can provide you with buckets to help you get started.”