Story & photos by Judy Benson

If you’re a Connecticut shellfish farmer, your ears might perk up a bit when you hear the term HABs – harmful algal blooms.

Toxic HABs outbreaks, sometimes referred to as “red tide” or “brown tide” because of the discolored water that can occur along with it, have caused recent shellfish bed closures around the country, including states neighboring Connecticut.

Connecticut has remained relatively sheltered from HABs thus far, but there have been sporadic, rare closures in isolated portions of the state. So while shellfish farmers and regulators here keep watch for any warning signs just in case, the rest of us can keep enjoying fresh clams and oysters grown in local waters, either from a commercial farm or harvested from certified recreational municipal beds.

“People can eat shellfish from Long Island Sound with confidence,” said Gary Wikfors, director of the Milford lab of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

That’s because of the well-coordinated early warning system in place in Connecticut to catch an outbreak of the particular kinds of algae that can sometimes emit toxins harmful to clams, oysters and mussels, and sicken the people who eat them.

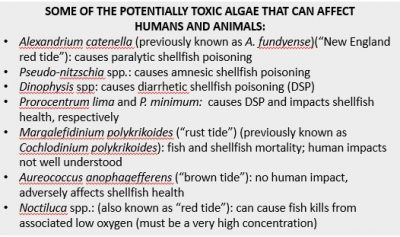

Algae, which range from seaweeds to tiny single-celled microalgae (also called phytoplankton), form the basis of the aquatic food chain. Among the thousands of different species, about 100 can contain or emit toxins into marine and freshwater bodies that can cause illness and even death in humans, pets and wild animals. Of these 100, a handful of are of greatest concern in Connecticut waters.

The mere presence of these types of algae isn’t a danger – most of the time a bloom occurs with no release of the toxin. But thanks to constant monitoring, there’s a system in place to respond quickly if that were ever to change. It’s a crucial part of ensuring the continued success of the state’s $30 million shellfish industry.

“The systems in use are very effective,” Wikfors said. “We haven’t seen HABs in Long Island Sound, but we don’t want to be complacent.”

So far, that vigilance has worked well at detecting blooms of these types of algae and alerting shellfish farmers and recreational shellfish commissions to be on the lookout. As recently as this summer, blooms of potentially harmful algae were found in waters of several towns from Guilford east to Stonington. But, as was the case in past years when this occurred, the bloom subsided and toxin was never detected.

“The monitoring of HABs exists so that we can act quickly to enact a closure if we ever need to,” said Tessa Getchis, aquaculture extension specialist for Connecticut Sea Grant. “We want to prevent costly recalls of product.”

She is also working with Sea Grant colleagues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island to develop materials on HABs for the media. Providing such information is important to making sure that what gets reported to the public is fact-based science, not alarmist, she said.

Emily Van Gulick and Kristin Russo, fisheries biologist and environmental analyst, respectively, at the state Department of Agriculture Bureau of Aquaculture (DABA), are the main line of defense against a harmful algal bloom spreading undetected in the coastal waters of Connecticut. The two lead a methodical monitoring program that entails regular collection of water samples in all coastal towns, microscopic analysis of samples and maintenance of a network to alert public health and shellfish regulators as well as volunteer commissioners as soon as possible. That could trigger shellfish bed and beach closures, among other steps.

Van Gulick noted that while Connecticut has so far been spared, this is no time for the state to let its guard down.

“HABs are increasing in frequency all over the world,” Van Gulick said. “People need to be aware of their environment and understand what’s going on. People should try to inform themselves about HABs, because they can have very serious impacts on your health.”

“HABs are increasing in frequency all over the world,” Van Gulick said. “People need to be aware of their environment and understand what’s going on. People should try to inform themselves about HABs, because they can have very serious impacts on your health.”

There have been no illnesses related to HABs in Connecticut shellfish. Many other states, however, are dealing with persistent HABs blooms that cause annual shellfish closures and threaten environmental health.

“We have to stay on top of it, because of what’s happening in surrounding states,” Van Gulick said.

For her part of the work, Russo collects water samples from all shoreline towns with active shellfish beds every other week from early spring through late fall, when water temperatures are most conducive to HABs.

“We take water samples in areas that best represent the shellfish growing areas, in at least one site in every town along the shoreline,” said Russo, as she lowered a plankton net into the water off the side of the aquaculture bureau’s 25-foot vessel Sea Hawk one morning in June.

Van Gulick said the public can help the state keep abreast of HABs, by reporting any time they see discolored water – which is usually caused by pollen in the spring and fall, but can be a sign of a HABs outbreak. But it’s not a reliable indicator. Wikfors said toxic blooms most often don’t cause a detectable change in water color.

Strange behavior in aquatic animals or animal kills, including shellfish kills, are another possible red flag. The state Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) is responsible for monitoring and responding to freshwater blooms. While the DABA routinely samples only from shoreline areas, Van Gulick and Russo will sample and test from freshwater bodies that are near Long Island Sound and have the potential to impact shellfish growing areas. People can use the reporting form on the bureau’s website, send photos and call directly.

“When we get calls about an area, we’re going to be sampling there,” she said. “It’s great having more eyes on the environment, because we’ve got to be careful.”

Judy Benson is the communications coordinator for Connecticut Sea Grant.

MORE INFORMATION:

- Additional information about HABs and HAB monitoring in Connecticut and the HABs reporting form can be found at: https://portal.ct.gov/DOAG/Aquaculture1/Aquaculture/Harmful-Algal-Blooms

- Additional information about DEEP monitoring and reporting freshwater blooms: https://ct.gov/DEEP/Water/Water-Quality/Blue-Green-Algae-Blooms

- To reach Emily Van Gulick by phone or email: (203) 874-0696 x125; Emily.VanGulick@ct.gov

- “Harmful Algae: A Compendium Desk Reference Executive Summary,” is available for download at: https://seagrant.uconn.edu/2017/08/09/harmful-algae-a-compendium-desk-reference-executive-summary/